Every once in a while something unexpectedly wonderful happens, and just such a thing has happened to photographic art enthusiasts living along the Front Range. Through 22 July, 2012, the Longmont Museum and Cultural Center is presenting Edward Weston: Life Work. The artwork is drawn from the collection of New York collectors Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg. Anyone ‘into’ art photography at all knows that Weston is considered by most art historians to be one of the demigods of 20th century photography. But the good news gets even better. When the Longmont exhibition first came to my attention I had assumed that the museum would mount a dozen or maybe a couple of dozen prints. The wonderful surprise is that this is a major exhibition consisting of over 125 original black and white prints.

The exhibition follows the life and artistic transformation of Weston. You see the struggling commercial portrait photographer morph into the bohemian photography artist. You see, in his portraits, still life, and landscapes, his turning away from the fuzzy, romanticized Pictorialist style that dominated American art photography in the decades that straddle the start of the 20th century. You see his art and focus influenced by his association with the art colonies of Los Angeles, New York, Mexico, and finally Carmel. You see, in his favorite nude models, his various lovers over the decades of his working career. You see him gain full stride, becoming one of the founding fathers of American Modernist photography, creating images that would help define and refine that era.

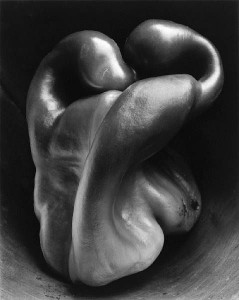

For all the changes in his life and art, the exhibit’s photographs show important constancy as well. Early on, Weston gained the ability to pre-visualize how colors, lights and shadows reflecting from the scene before his camera could be rendered into a luminous range of black and white. Early on, he mastered the skills necessary to capture those tones onto film and then onto print. But by far the most important constant in his art life, and the most important reason that he is so revered by art photographers everywhere, was his genius in seeing in the most ordinary items—even a bed pan for heaven’s sake—the possibility of a connection with the human psyche. His artistic brilliance then is not just the ability to render his subjects in spectacular gradations of black and white, but his ability to portray those subjects in such a way as to force the viewer to look upon the prints not only with his eyes but with his mind’s eyes as well.

Weston astonishes us with peppers that mimic the human form, beguiles us with nudes whose sexual energy is tempered by the beauty of shape and tonal range, charms us with portraits that that reveal the person as well as capture his reflection, and connects us at a deeper level with nature with landscapes that that expose beautiful patterns and sublime gradations of black and white that usually are concealed by the tyranny of color. As a consequence his photography is far more than eye-pleasing documentation of the objects before his camera. Rather, his art speak of our relationships to the world around us and of our relationships to each other. As a note on one of the exhibit wall states: “Where others saw nothing of note, Edward Weston caught the rhythms, patterns, and interconnections between nature and human experience. Whether exploring still life, the human face, the landscape or the nude, his goal was never a literal recording.”

This is a marvelous exhibition, more wonderful for the unexpected breadth and the depth of its coverage of Weston’s career. Since such an exhibition will likely not be presented in Colorado for quite some time I can’t image that anyone in the I-25 corridor from Wyoming to New Mexico who cares about photography as an art form would fail to take this opportunity to view firsthand this significant and extensive presentation of Weston’s most important work.