Recently I had the pleasure of taking in an exhibit at the Longmont Museum featuring two “American Visionaries”, photographer Dorothea Lange and her one-time husband, the artist Maynard Dixon.

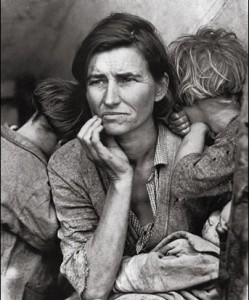

As expected, the exhibit featured many of Lange’s FSA-era photographs; after all these were the photographs that admitted Lange to the pantheon of early 20th century American photographic gods. Foremost among her FSA-era photographs on exhibit was the iconic Migrant Mother.

Iconic. That word is rarely far away when Migrant Mother is mentioned.

Reflecting on Migrant Mother started me thinking about the role of the ‘iconic’ work in the making of an art ‘god’. Certainly most renowned artist have at least one iconic piece, the truly greats usually more than one. Michelangelo has David, The Pieta and Sistine Chapel, Da Vinci, The Mona Lisa, Warhol, Campbell Soup and Marilyn. But some famous artists have none. The city of Denver is loopy over the honor of hosting the Clyfford Still Museum and its collection of Still’s abstract art. But I wonder how many museum patrons, when asked which was Still’s iconic painting, would identify the same image. Of course Still’s titles, like 1957-J-No. 2, don’t exactly aid his paintings in gaining membership into the brotherhood of iconic art.

My musing over iconic images soon returned to photography, my chosen art. Can a photographic artist be elevated to deity or even demigod status, I wondered, without having created at least one universally recognized—within the art world universe at least—iconic image? I mentally rifled through the early 20th century gods: Stieglitz (The Steerage), Steichen (The Pond), Adams (Moonrise, Monolith), Watson (Pepper), and Strand (Wall Street), Evans (Allie Mae), Lange (duh). Check, check, check, check, check, check, and check. I quickly scanned the mid-century artists: Callahan, White, Weegee, Capa, Smith, Frank, Cartier-Bresson, Brandt. Check them all off. Late-Modernist? Robert Adams, Winogrand, Friedlander, Arbus? Yup. Postmodernists Prince, Kruger, and Sherman? Check, check, and check.

So they all have at least one iconic image. But does that make an iconic image a pre-requisite for fame? Certainly no one would entertain the idea that one great photograph by itself can make the artist. Just look at how many great photographs, by photographers you’ve never heard of or will ever hear of, can be found on Flickr. Certainly a significant number of really important images (‘important’ by whatever standards photo art historians employ) must be the primary basis for admittance into the pantheon. But among those ‘significant numbers’ must there be at least one universally acknowledged ‘memorable’ photograph, an image that epitomizes the artist’s legacy, before that legacy can elevate the artist to the status of god?

I searched my memory for counter examples. The Bechers came to mind. Bernd and Hilla Becher were a husband and wife photography team who gained fame for their exhaustive typological series of aging industrial structures, especially water towers, in post-war Germany. I suppose one could argue that no one of those numbingly similar water tower images constituted the ‘iconic’ water tower. On the other hand, it could be argued that any one of those water tower images, just because they were so numbingly similar, constituted the iconic image. I think that latter position would win since if a photo historian were to be presented a mug shot of an aging water tower, I’d bet that the first name he’d come up with is ‘Becher’.

As I stood there in the Longmont Museum, gazing at Migrant Mother, that most iconic of iconic photographs, I concluded that yes, a photographic artist must do more than stir the art world. The artist must create at least one image that will be remembered, an image that will be conjured whenever and wherever the artist’s name is mentioned. If he or she is to gain lasting fame, the photographic artist must capture an iconic image.