If it is to be successful, a photography exhibit, much like an individual photograph, must not only be visually compelling, but also make some connection to the human experience. As a collection of visual art, the first requirement is self-evident. If the exhibit’s photographs don’t intrigue the eye, viewers will not engage with the images long enough for a deeper, mindful connection to take hold. On the other hand, thanks primarily to the Internet, today most people suffer from sensory overload and visual numbness. Hence, eye-pleasing aesthetics and composition alone will no longer hold a viewer’s attention for very long. The mind must also be engaged at a deeper level if the exhibit is to offer a truly absorbing experience.

On exhibit at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts through November 13, 2022, is a small exhibit curated by Dr. Sarah Kennel (VMFA’s recently appointed Aaron Siskind Curator of Photography and Director of the Raysor Center) that superbly checks both boxes. The Architecture of History: Photographs of Francis Benjamin Johnston and Keris Salmon asks viewers to reflect on the connection between the elegant homes and plantation manors of the 18th and 19th century slave holding class, and the enslaved peoples who built those edifices and whose labor was the basis for the wealth that afforded them. This exhibit continues a movement led by VMFA to exhibit fine art in a larger, more inclusive context that recognizes the too-long ignored contributions to society (and to art!) of too-long marginalized peoples.

The eight photographs of mid-20th century photographer Francis Benjamin Johnston are particularly striking, and do the heavy lifting with respect to captivating the eye in this exhibit. The photographs are drawn from Johnston’s survey of the architecture of the Old South, accomplished in the 1930s through mid-40s. She captured the fading glory of the colonial and antebellum South before it was lost to time, progress, and fire. The large (~20”x16”) gelatin silver prints are elegantly matted and framed. Captured by Johnston’s enormous 8×10 view camera, each image is a feast for the eye, offering beautiful composition, exquisite natural lighting, and extraordinary detail. A case in point is Old Quarters, Falmouth. But as the text that accompanies her photographs notes, Johnston also captured “competing visions of the South”. Photos like Brick Cabins, Fredericksburg show dilapidated buildings and other signs of social inequities that reflected “the enduring effects of segregation and poverty”, and “proved the need for progressive reform.”

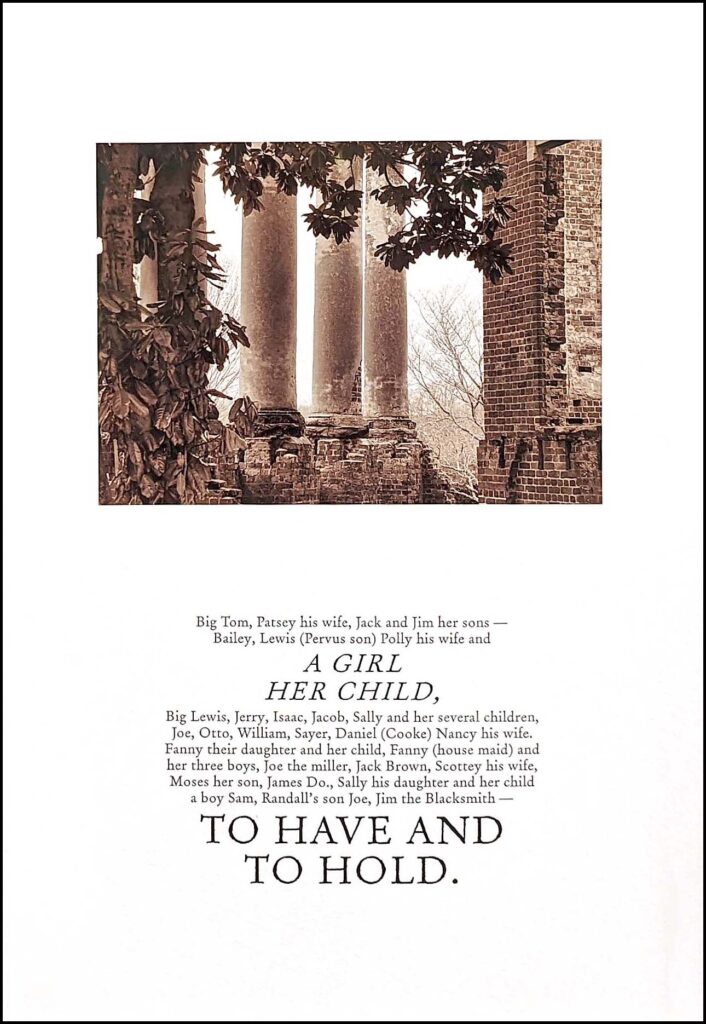

The nine works of Keris Salmon, while neither as visually compelling nor as consistently ‘architectural’ as those of Johnston, attend to the mind even more deeply. Each art piece is a beautifully framed and matted ~12×18 print that is composed of a ~9”x6” inkjet photograph accompanied by text in elegant letterpress. A fine example is To Have and To Hold. It is Salmon’s text that makes clear at what cost to enslaved people the elegance that is captured or implicit in her photos was attained. Salmon is an African American married to a direct descendent of a slave-owning plantation owner. Thus her work is not merely dispassionate photojournalism, but rather is deeply personal storytelling.

This exhibit is small but powerful. It shows that we can expect wonderful things from VMFA’s new curator of photography. See the exhibit if you can.