When photography art historians create a short list of the great street photographers of the 20th century you can be certain that right there along with the renowned European masters, Atget, Brassai, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Frank, will be an American, Garry Winogrand. Art historian Ian Jeffrey has referred to Winogrand as “a compelling artist, and without parallel in the medium”. Photo historian Robert Hirsch has said that Winogrand’s body of work “radically redefined the social landscape.” Winogrand’s work has been presented in scores of books and exhibitions, including over a half dozen solo or group exhibits at the New York Museum of Modern Art.

On exhibit at the Denver Art Museum through September 16, 2012 are forty eight of Winogrand’s large (approx. 8×12) full-frame gelatin silver prints drawn from the DAM’s permanent collection. The exhibit takes its title and theme from Winogrand’s 1975 book Women Are Beautiful.

For every iconic street image, whether it is Frank’s Trolley – New Orleans, 1955, Cartier-Bresson’s Behind St. Lazare’s Station, 1932, or an image that can be seen at the DAM exhibit, Winogrand’s Histrionics on Bench, 1975, the overriding first reaction to the photograph is wonder over the chance of capturing such a fleeting scene. To non-photographers, such improbable capture must seem like pure luck. And there is no doubt that luck is involved because street photographers essentially must create their own haystack of literally hundreds upon hundreds of images and then sift through them all to find the ‘needle’ that is the image we ultimately see in the book, exhibit, gallery or museum.

Street photographers unashamedly take advantage of the fact that in photography there is some chance, however small, that each click of the camera will result in a brilliant image. Determined street photographers then multiply that small chance by thousands of clicks. Winogrand certainly increased his odds by photographing, as Hirsch put it, “machine-gun” style. Winogrand reportedly captured hundreds of thousands of images before his premature death in 1984 at age 56 due to gall bladder cancer. With his legendary Leica, Winogrand apparently photographed everything and everyone he encountered. He once famously said “I photograph to find out what something will look like photographed.”

The art of the street photographer then is the art of the contact sheet—the art of finding of ‘art’ buried amongst hundreds and hundreds of artless photographs.

Acknowledging the role that the ‘numbers game’ plays in their art is not a put-down of street photography artists. The good ones do more than just take gobs of photos and cross their fingers. The good ones add instinctive compositional skills, a sixth sense for anticipating special moments and, most importantly, a story to tell to the numbers game. This greatly increases the odds of finding art in their contact sheets. However, the great 20th century street photographers, the Cartier-Bressons, the Franks and the Winogrands, added even more. Their gift—their true art—was their ability to find in their contact sheets not just an artful image, but rather something new in photography. For Cartier-Bresson it was the capture of the ‘decisive moment’, for Frank it was a contrarian view of American society in the 50’s, and for Winogrand (whose primary body of work was in in the 60’s and 70’s) it was a new way to portray what Washington Post photography columnist Frank Van Riper once described as the ‘angst and ennui’ of the post-nuclear, post-innocence America.

Of course the nominal subjects of the 48 images in the DAM exhibit are women. Winogrand clearly had a soft spot for the fairest of the fair sex. He clearly relished capturing beautiful young women and beautiful less-young women in everyday poses, in everyday unguarded moments, going about their business. But what make these photographs special is not so much their subjects but rather the way these photographs are composed, or, more accurately, not composed. For even in DAM’s tiny sample of Winogrand’s work (tiny at least relative to his prodigious output) you can see evidence of the startling helter-skelter composition—the ‘grab-shot’ look if you will—that is the hallmark of his work.

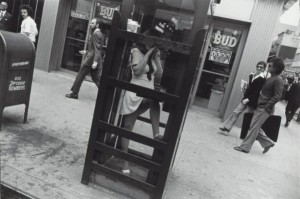

NYC (Woman in Phone Booth, Leg Up), Garry Winogrand, 1972

A case in point is NYC (Woman in Phone Booth, Leg Up), 1972. The center of attention in this photograph is an attractive woman making a call in a phone booth on a busy street corner. The woman is standing with one leg down and the other up and resting against the booth wall. The effect of her raised leg is to hoist her short skirt so that we see lots of shapely leg. But that is not what makes the image compelling. What makes the image compelling is that the actual horizon is skewed tens of degrees. Everything in the image, buildings, passers-by, mail box, signs, and, of course, the phone booth is cocked at a strange angle. Everything and everybody except the young lady, that is. Somehow, improbably, she appears to be standing straight. It’s an optical illusion of course, probably caused by the angle of her raised leg. The illusion however makes for a wonderful photograph, a photograph that causes your eyes to continually wander around and then return to the puzzle that is the woman in the booth.

Histrionics on Bench, Garry Winogrand, 1975

Another example in the exhibit is Winogrand’s iconic Histrionics on Bench, 1975. This photograph captures eight people on a park bench: a young woman, five teenage girls, and two males (one on each end of the bench). But the six females (actually the actions of the females) are the real subjects of the photograph; the males are merely bookends and foils. And what fascinating subjects the females are. The young woman is engaged in lively conversation with the male to her right (image left). Next to her are three huddled teenage girls. Two of the girls are whispering to each other as one of them comforts a third girl who appears distraught. Next to them are two girls who seem to be checking out something or someone off-image to their left (image right), likely some hunky guy. Again, as in NYC (Woman in Phone Booth, Leg Up), 1972, the composition is off-kilter. The horizon, which can be seen in the background, is cocked at such an angle that the eight on the bench should be falling off the bench’s right edge. The only one of the eight who is fully facing the camera, an elderly male reading a newspaper, is cut in half by the photograph’s right edge. Yet the photograph works. It works wonderfully well. The dynamism and un-orderliness of the composition matches the dynamism and un-orderliness of the six young women.

The very lack of classic composition was Winogrand’s way of seeing, his way of dealing with a country and a society that had lost its composure due to Hiroshima, Viet Nam, the Cold War, the Civil Rights Movement, and the assassination of a president. If society’s energy and angst and confusion sometimes spilled over the edge then too sometimes Winogrand’s images would as well. His was a new way of portraying society, and it was his gift to photography.

DAM’s exhibit is small, but Garry Winogrand – Women Are Beautiful is a beauty itself. See it if you can.